Project

Crosstown Redesign

In December 2016, a pedestrian was struck by a car and killed in a hit-and-run accident while attempting to cross the intersection at Coming Street and Septima P. Clark Parkway. Sadly, this tragic incident marked the third pedestrian fatality at this intersection since the City of Charleston completed its Parkway beautification project in 2013. After each death, residents and community leaders have called for safety improvements at this intersection; however, only one proposal – calling for a second pedestrian overpass over the Parkway – has been brought to the table. The proposed bridge would be constructed just two blocks from the existing bridge, which was built in the 1970s.

The Coastal Conservation League has analyzed the systemic safety issues along the entire mile-long route and proposes a series of solutions to these problems that will improve safety and connectivity for the neighborhood, which has been negatively impacted by the Parkway, also known as the Crosstown Expressway, since its construction cut its way through the upper peninsula nearly a half-century ago.

The Road’s History

Completed in 1968, the Crosstown unified Coastal Highway US-17, which originally stopped at the Ashley and Cooper Rivers and required drivers to navigate through downtown city streets. The Federal Highway Administration and South Carolina’s Department of Transportation (DOT) had previously decided to terminate the new I-26 near the peninsula’s Line Street, so the agencies designed the Crosstown to serve as a connection between US-17 and I-26.

The path selected for the Crosstown Expressway sliced diagonally across the upper peninsula through a predominantly African American neighborhood, displacing approximately 150 residences and businesses. A once unified neighborhood of working-class homes and businesses was subsequently divided by a six-lane expressway, and the upper peninsula’s historic street grid was obliterated.

Today, three neighborhood public schools are located north of the Crosstown, forcing children who live south of the Crosstown to risk their lives crossing the road each day. In 1974, after a number of collisions, a pedestrian overpass was constructed in order to prevent pedestrians from running across the road. Yet, its effectiveness is questionable. The Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center (PBIC) has suggested that many pedestrians will not use an overpass if they can cross at street level in about the same time. Further, the cost of constructing and maintaining overpasses can be very expensive due to the need to accommodate all persons, as required by the Americans with Disabilities Act.

A Phased Approach to Safety

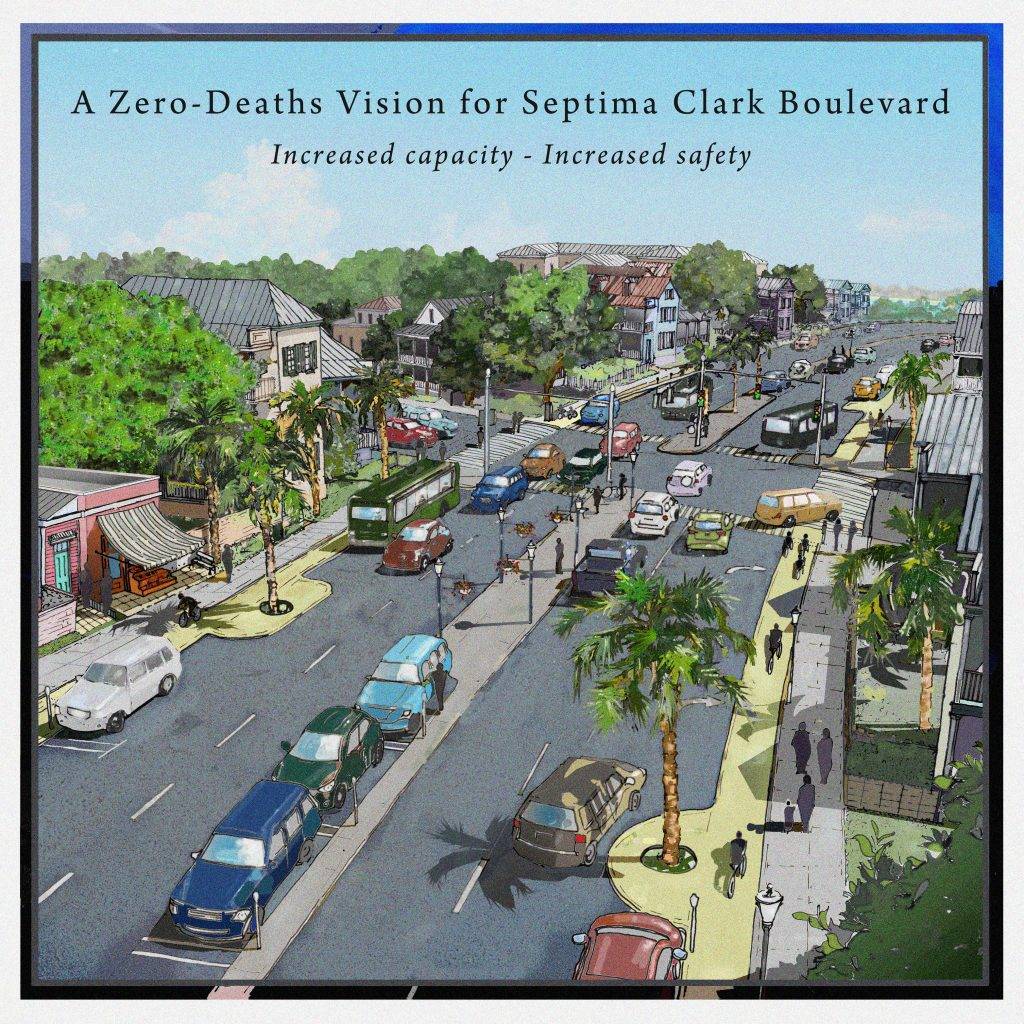

Considering the number of people who live and work on either side of the Crosstown, a new safety approach must be taken to prevent further loss of life. To provide safe pedestrian and bicycle access and to reconnect the severed neighborhood, the Conservation League proposes a series of redesign phases for the Crosstown and its intersections.

Phase I

- Adjust signals at all intersections to provide advanced crossing for pedestrians and bicyclists ahead of automobile turning lanes

- Reduce speed limit from 35 mph to 25 mph with subsequent enforcement

- Remove fencing along the right-of-way to provide greater access to the park, residences and commercial buildings adjacent the route

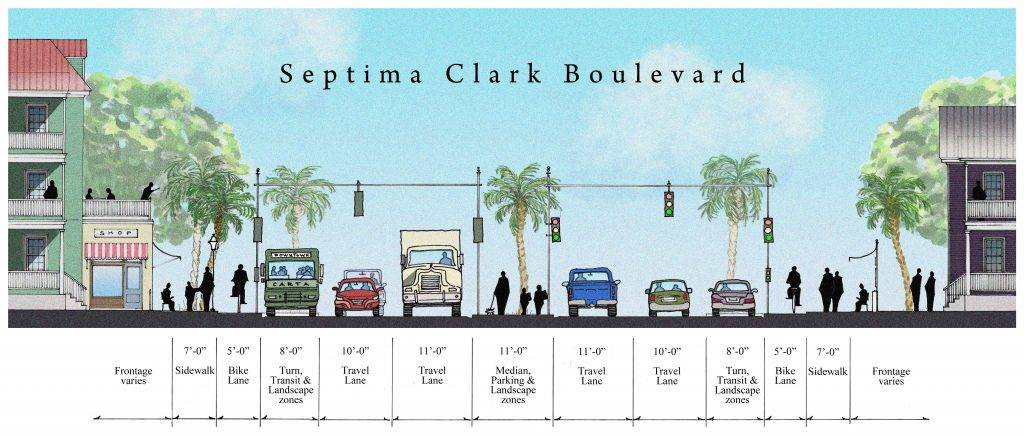

- Narrow travel lanes down from 12- and 14-feet to 11-feet

- Install dedicated bike lanes in both directions

- Complete Hagood connection

Phase II

- Convert Ashley Avenue, Rutledge Avenue and Coming Street from one-way to two-way roads

- Connect Ashe Street to Sheppard Street by creating a new intersection, similar to the Hagood connection

- Remove on- and off-ramps at Coming Street, Sheppard Street and Line Street

- Designate Cosgrove Avenue/SC-7 an alternate US-17 bypass

- Transfer control of the Crosstown from SCDOT to the City of Charleston

- To protect bike lanes and further calm traffic, replace the Crosstown’s outer lane with on-street parking, curb bump-outs and landscaping

- Create a CARTA bus route with stops along the Crosstown

Phase III

- Remove Spring and Cannon overpasses leading to Ashley River Bridges

- Remove King Street overpass and redesign connection to the Ravenel Bridge

- Remove the Crosstown’s pedestrian overpass

This phased approach provides a series of action items that can be implemented immediately by the City of Charleston at a cost lower than the price of a single pedestrian over- or underpass constructed at just one intersection.

Phase I improves safety at the intersections by giving pedestrians and bicyclists priority over automobiles and slowing cars down along the route without reducing capacity. By slowing cars down to the same speed as every other street on the peninsula, the City of Charleston can transform the Crosstown from a blight-inducing urban highway into a neighborhood “Main Street” for the upper peninsula.

Phase II further improves neighborhood connectivity by restoring Ashley Avenue, Rutledge Avenue and Coming Street to two-way traffic. Creating a new intersection between Ashe and Sheppard Streets achieves a safe at-grade crossing in the block between Rutledge Avenue and Coming Street like the new Hagood connection. This new connection eliminates the need for a new pedestrian overpass.

Phase II’s removal of the on/off ramps along the route transforms the design from a limited access expressway to a traditional urban boulevard. Traffic would turn onto and off of the route at intersections, rather than short access roads that lack traffic signals and place pedestrians and bicyclists at significant risk.

Phase II’s transfer of control to the City of Charleston and its designation of the Crosstown as an alternate US-17 bypass route, similar to Myrtle Beach, gives the city the authority to properly maintain the road as a neighborhood street without reducing capacity along the heavily traveled Coastal Highway. This will allow city leadership more control over further traffic calming designs, such as replacing the outer lanes with on-street parking, bus stops and new curbs, and landscaping to protect pedestrians and bicyclists.

The final phase will be the most transformative for the upper peninsula. Phase III calls for the removal of the overpasses onto and off of the Ashley River bridges on the west side and the King Street overpass on the corridor’s east side. By restoring at-grade intersections at these locations, the Crosstown will officially be redesigned to function as an urban boulevard like Calhoun Street instead of a high-speed expressway through a residential neighborhood.

The Conservation League’s goal is to provide safe pedestrian and bicycle access along and across the Septima P. Clark Parkway and to reconnect the neighborhood split by the expressway. This goal to develop and implement a design that works for both residents and commuters can and will be accomplished by working with the communities impacted by the Crosstown and the elected officials that represent these surrounding neighborhoods.

Learn more about the Crosstown here:

“Reverse the divisive legacy of the Charleston Crosstown”

“Hagood Avenue might become key connection from West Side to medical district”

“Do pedestrians need a new bridge?”